Lack of regulations and increased fishing pressure likely to blame

Herbivorous parrotfish play critical ecological functions in sustaining resilient coral reefs which protect coastlines, provide food and support livelihoods. However, in The Bahamas, parrotfish are increasingly being targeted and to date, no fishery regulations have been implemented.

Assessing the distribution, diversity, abundance and habitat use of parrotfish are important for preserving coral reefs and to provide input for managing fishing pressure on their populations.

The Perry Institute for Marine Science (PIMS) is excited to share that Dr. Krista Sherman, Maya Gomez, Thomas Kemenes and Dr. Craig Dahlgren recently published a new open access article entitled, “Spatial and Temporal Variability in Parrotfish Assemblages on Bahamian Coral Reefs”, in the journal Diversity.

PIMS has been monitoring the status of reefs throughout The Bahamas for decades using Atlantic & Gulf Rapid Reef Assessment (AGRRA) surveys. Our team analyzed AGRRA data collected between 2011 and 2019 to examine the status of parrotfish populations across 26 reefs around two islands in The Bahamas; New Providence and Rose Island. We also sought to determine whether the growing fishery has impacted parrotfish populations.

Key findings revealed a 59% decline in parrotfish density and noticeable changes in size composition over time, with a shift to smaller size fish and loss of large adults across reef sites. The authors reported that “only 3% of parrotfish were large/terminal phase adults”. These changes were evident in both ecologically important parrotfish species as well as others that are being caught for subsistence and commercial fishing.

So why is this alarming? Parrotfish populations in The Bahamas have typically been among the most abundant in the Caribbean, but these latest results demonstrate that mean densities around many (58%) of the reefs surveyed are now lower than regional values with significant declines occurring in a few parrotfish species. Additionally, large parrotfish are known to be more effective at grazing (i.e. removing macroalgae) than smaller fish, so the loss of these large herbivores has implications for the condition or health of coral reefs habitats.

Dr. Sherman, lead author and Senior Scientist for PIMS’ Fisheries Research & Conservation Program, said, “Our results highlight the importance of monitoring and emphasize the urgency of implementing science-based strategies to sustainably manage the fishery and protect these ecologically essential herbivores, which are vital components of coral reefs.”

To learn more about the suggested management recommendations and additional results read the paper and visit perryinstitute.org.

Green Turtle Cay Travel Guide for Divers

Plan your diving trip to Green Turtle Cay, Bahamas. Discover the best dive sites, coral reefs, how to get there, where to stay, and why this Abaco island is a hidden gem for underwater adventure.

How to Volunteer for Coral Reef Restoration

Want to help restore coral reefs? Here’s how to volunteer with PIMS and the Reef Rescue Network, from dive-based restoration trips to snorkel programs, citizen science, and remote support.

Become a PADI Dive Instructor in The Bahamas | Conservation-Focused IDC

Become a PADI Dive Instructor in The Bahamas | Conservation-Focused IDC | Perry Institute for Marine Science Education & Training Ready to take your diving skills to the next level

Stream2Sea Coral Care: The World’s First Reef-Positive Sunscreen

Stream2Sea Coral Care: The World’s First Reef-Positive Sunscreen | Perry Institute for Marine Science Conservation Partners Stream2Sea Coral Care: The World’s First Reef-Positive Sunscreen Discover why PIMS has partnered with

Build a Coral Reef for the Holidays | PIMS x Partanna

PIMS is partnering with Partanna to build a 100m² carbon-negative reef. Rick Fox is matching donations up to $25k. Help us build a sanctuary for the future.

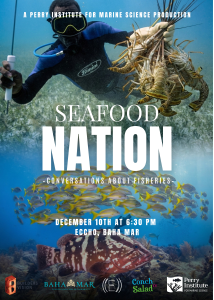

“Seafood Nation” Documentary Premiere Explores the Heart of Bahamian Culture and the Future of Fisheries

NASSAU, The Bahamas | December 5, 2025 – From the bustling stalls of Potter’s Cay to family kitchen tables across the archipelago, seafood is far more than just sustenance in