By Hayley-Jo Carr

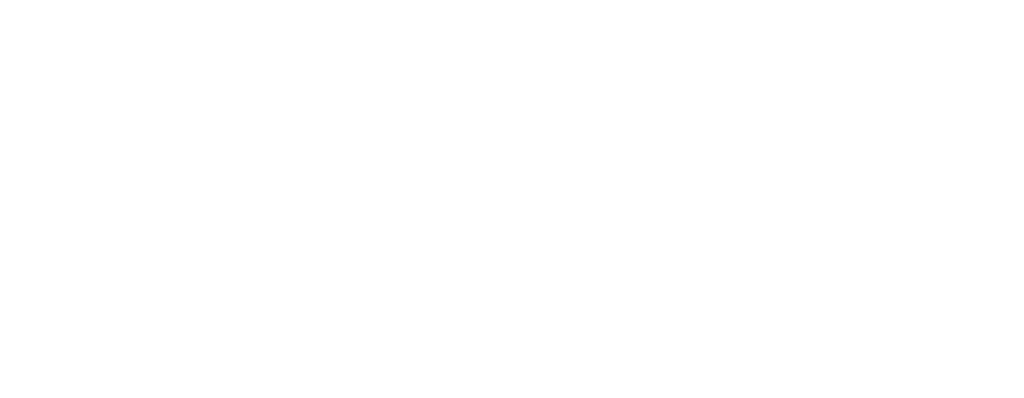

The Longspined Sea Urchin, Diadema antillarum, provides essential ecosystem services to coral reefs, however populations have seen drastic reductions in numbers due to a disease outbreak in the 1980s. Restoration efforts are underway to assist in restoring local populations of this important grazer.

Diadema antillarum is a species of sea urchin within the Family Diadematidae, found throughout the Caribbean and regions of the Atlantic Ocean such as the shallow waters of The Bahamas. This sea urchin was abundant on coral reefs for thousands of years up until 1983 when a disease caused mass mortality wiping out up to 97% of mature individuals across the region. This mass mortality, thought to be caused by a water-borne pathogen that has yet to be identified, is one of the most dramatic natural declines ever recorded in a marine species.

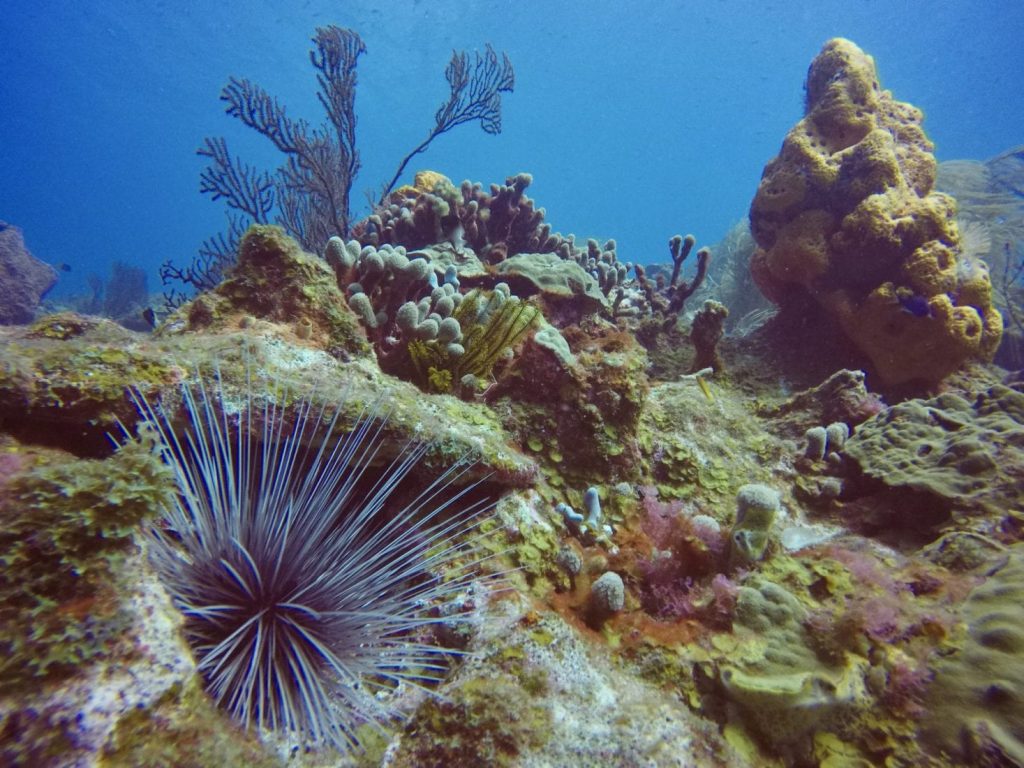

The reason D. antillarum is so vital to coral reef ecosystem health is that they are a herbivorous species that graze on the macro algae that overgrow reefs; without them, coral reefs may become smothered in algae. Algae kills corals by reducing sunlight and trapping sediments on the reef. The urchins’ feeding activity cleans and scrapes the limestone substrate, and in turn stimulates settlement of coral and other invertebrate larvae; since the mass D. antillarum die-off there has been a huge reduction of larval coral settlement as a result. The reduction of this species is one of the main contributing factors as to why Caribbean reefs are now, sadly, more algae-dominated than coral-dominated.As their common name states, this urchin has very long hollow spines. At the base of the urchin are branched tentacles called tube feet, which help in gathering food, respiration, moving and mucous production. Mainly nocturnal feeders, as they are extremely sensitive to light, they generally hide within the reef in the day and then venture out at night to feed, so you are more likely to see them during night dives when they are extremely active.Their long spines provide protection against predators and the mucous coating on the spines carries a mild poison to help deter smaller predators. Known predators include the queen triggerfish (Balistes vetula), Caribbean spiny lobsters (Panularis argus) and Caribbean helmets (Cassis turberosa). D. antillarum are often observed in large congregations as this is thought to help protect against attacks by predators. Congregations can also be observed during spawning seasons in the summer when eggs and sperm are released into the water where they are fertilized and develop into larval echinopluteus (baby urchins)!

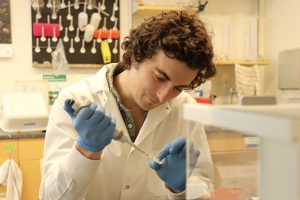

HOW WE CAN HELP Human interventions may be able to assist the natural recovery of this key species, which is so vital to keeping algae growth on reefs under control. From breeding programs to relocation activities this is an active area of research currently being fine-tuned to find the most successful application.The Perry Institute for Marine Science is actively working with partners to establish best restoration practices. One such practice is the process of relocating D. antillarum from areas with high human impacts or development, such as marinas and shorelines facing hotel, housing or industrial expansions. Another area to source from is rocky shorelines with little to no coral cover. Individuals can be carefully gathered from these sites and relocated onto coral reefs, particularly reefs with high algae cover and low herbivores. Extra care must be taken when handling these urchins to avoid being punctured by the spines and to avoid damage to the urchin. One safe method is to use two pieces of wood to almost create giant pincers that you can carefully place either side of the urchin and then lift into a basket. The urchin should be mobile before trying to remove it, as this is when the tube feet are not suctioned as strongly to the substrate. Containers of seawater are used to transport the urchins to their new home.

Note: This urchin was immediately returned to the water after photo was taken.

Once relocated these urchins have positive ecological effects on the reefs; in the short term, these urchins drastically reduce the amount of macro algae on the reef and in the long-term, this bolsters coral cover because the substrate is more favourable for coral larval settlement. Many studies have also shown an increase in crustose coralline algae (CCA) on reefs with high populations of D. antillarum. CCA is important because it typically crusts over and between fragments of coral, and essentially cements reefs together. What’s more, coral planulae (i.e., baby corals) seem to prefer settling on this type of algae.

Relocating D. antillarum is one way to assist in restoring populations back onto coral reefs, however more captive breeding and release programs are needed to increase numbers to pre 1980 population levels. Without a doubt, ongoing human intervention is required to assist in the recovery of these super spikey cleaners.

All Photos by Hayley-Jo Carr.

New Reef Rescue Sites Take Root in Barbados and Grenada

Barbados Blue and Eco Dive Grenada dive shop owners Andre Miller and Christine Finney (Credit: Eco Dive) Reef Rescue Network Expands to Barbados and Grenada The Perry Institute for Marine

The Bahamas Just Opened a Coral Gene Bank—Here’s Why It Matters

The nation’s first coral gene bank will preserve, propagate and replant coral to reverse devastation from rising ocean temperatures and a rapidly spreading disease Video courtesy of Atlantis Paradise Island.

This Is What Conservation Leadership Looks Like

From Interns to Leaders: How PIMS is Powering the Next Generation of Ocean Advocates Taylor photographs coral microfragments in the ocean nursery, helping monitor their fusion into healthy, resilient colonies

When Ocean Forests Turn Toxic

New study in Science connects chemical “turf wars” in Maine’s kelp forests to the struggles of Caribbean coral reefs — and points to what we can do next Lead author,

Who’s Really in Charge? Unpacking the Power Struggles Behind Madagascar’s Marine Protected Areas

Researchers head out to monitor Marine Protected Area boundaries—where science meets the sea, and local stewardship takes the lead. The Illusion of Protection From dazzling coral reefs to centuries-old traditions,

PIMS and Volunteers Step Up as Legal Battle Leaves Barge Grinding Reef in Fowl Cays National Park

Worn out but undefeated, the cleanup crew rallies around their paddleboard “workbench” in front of the stranded tug and barge—a snapshot of community grit after hours of underwater heavy‑lifting. Photo