The Illusion of Protection

From dazzling coral reefs to centuries-old traditions, Madagascar’s coastlines are some of the most vibrant and culturally intertwined marine environments on the planet. But within its Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), a stark reality lingers beneath the surface: legal protection doesn’t always translate into real-world results.

A new peer-reviewed study titled “Authority, capacity, and power to govern: Three marine protected areas co-managed by resource users and non-governmental organizations” (Marine Policy, 2025) explores this issue in depth. The research was led by Jean Aimé Zafimahatradraibe, his colleagues Malagasy scientists from the country’s only marine science institute and co-authored by our very own Senior Scientist at the Perry Institute for Marine Science, Dr. Aaron C. Hartmann, with:

Lala N.J. Ranaivomanana, Institut Halieutique et des Sciences Marines (IH.SM), Université de Toliara

Cicelin Rakotomahazo, IH.SM, Université de Toliara

Bemahafaly Randriamanantsoa, Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), Madagascar

Gildas G.B. Todinanahary, IH.SM, Université de Toliara

The findings? Community-led protection of marine ecosystems like coral reefs has promise, but without resources, support, and enforcement, it’s like trying to plug a leaky boat with paper.

“We often assume that giving communities legal authority to manage the ocean means they have the power to protect it,” said Dr. Hartmann. “But Jean Aimé and the team found that authority without resources or real influence can be just as ineffective as no authority at all.”

Co-Managing the Ocean: A Bold Yet Fragile Model

With limited government capacity to manage its vast coastal ecosystems, Madagascar developed a pioneering legal framework that allows local communities—known as COBAs—to manage MPAs in partnership with NGOs. The model is celebrated for decentralizing governance, embedding local knowledge, and enlisting global conservation support.

It’s a promising setup. But for co-management to succeed, the governance groups comprised of local communities and advised by NGOs must have:

Authority — The legal right to make decisions

Capacity — The training, tools, and infrastructure to carry them out

Power — The actual ability to enforce decisions and effect change

This study reveals that more than half the time, international NGOs are in the driver’s seat and making decisions. When communities are handed the wheel, they have no engine, no map, and no fuel.

Data Dive: Who’s Governing, and How Well?

Using the Natural Resource Governance Tool (NRGT), the research team evaluated governance effectiveness in three MPAs:

Soariake (Southwest Madagascar)

Ankivonjy (Northwest)

Ankarea (Northwest)

Governance Scores by MPA

Soariake scored relatively well, with moderate authority, strong capacity, and some enforcement power.

Ankivonjy and Ankarea fell short in most areas—scoring at or below zero across nearly every metric.

“In Soariake, there’s at least a base to build on,” Hartmann noted. “But in the other two locations, the governance groups are struggling with the basics—enforcement, participation, and even engaging in conversations about how to govern.”

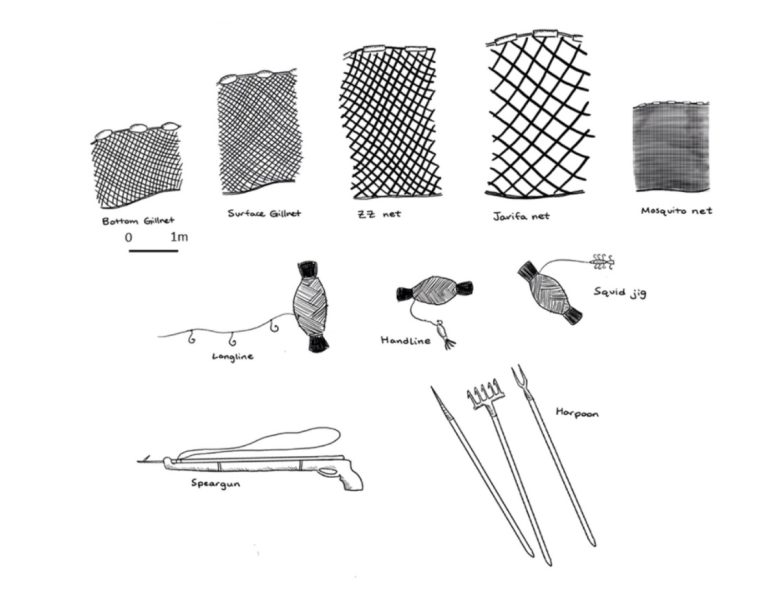

More Gear, Less Protection: Fishing Pressure and Regulation

The study also assessed ecological protection levels using the Regulation-Based Classification System (RBCS). It found that MPAs with a wider variety of fishing gear types—especially destructive or unregulated gear—tended to have weaker protection overall.

Soariake had the highest fishing effort (105+ pirogues/day), yet its stronger governance kept things somewhat in check. Ankivonjy and Ankarea, meanwhile, faced rampant illegal fishing, including the use of scuba for sea cucumber harvesting and banned gillnets.

TLDR: more types of gear = lower levels of effective protection. Even so-called “protected” areas are at risk if rules aren’t enforced.

The Role of Customary Law—Powerful, but Incomplete

In Madagascar, traditional systems of regulation still hold weight. Local laws known as Dina govern community resource use, and sacred cultural taboos (fady) designate no-fishing days or prohibit harvesting certain species.

For example, in Ankivonjy, Thursdays are sacred—a fady day where no fishing is permitted. It’s a powerful social norm, but without backup from formal governance systems, it can’t stop determined violators.

“Local traditions like Dina and fady can align with conservation priorities as a by-product,” said Dr. Hartmann. “But these traditions can be eroded when communities lose trust and security.”

Why This Matters: Lessons for Global Marine Protection

With the world aiming to protect 30% of ocean areas by 2030 through the global 30×30 pledge, this study arrives at a crucial time. It shows that MPA designations alone aren’t enough—we need meaningful, enforceable governance.

Madagascar’s MPAs reveal a wider truth: when enforcement is weak, when communities are under-resourced, and when co-management lacks coordination, even the best-laid plans falter.

This result aligns with findings from similar community-led MPA efforts in the Philippines, Kenya, and Indonesia, where strong outcomes depend on:

Legitimate authority

Technical and financial support

Stakeholder trust and engagement

The PIMS Perspective: Science + Community = Resilience

At the Perry Institute for Marine Science, we believe science should serve communities. Our conservation work around the world centers on building resilient ocean ecosystems through collaborative conservation.

We’re proud to support research like this and invest in:

The Reef Rescue Network – Coral restoration at scale and around the world

Mangrove restoration – Rebuilding coastlines and carbon sinks. See our work as part of The Bahamas Mangrove Alliance

Science-based monitoring and governance – Ensuring protection is measurable and meaningful

“True marine protection is less about drawing boundaries and more about building capacity,” said Dr. Hartmann. “We need to equip communities with the tools, training, and trust to lead the charge.”

Take Action

🟢 Donate to Support Marine Conservation

🟢 Volunteer with PIMS

🟢 Learn more about Community-Led Conservation

Every reef, every mangrove, every island, and every fishing village counts. Join us in helping communities protect what matters—before it’s too late.

Gratitude to Our Funders

This research and the broader conservation work would not be possible without the generous support of our funding partners. We thank the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), the MacArthur Foundation, the Pêche Côtière Durable project, and the Coral Reef Research, Education and Conservation Team (CoRRECT) at the Institut Halieutique et des Sciences Marines of the University of Toliara. We are also grateful for financial contributions from the Belmont Forum through the National Science Foundation (RISE-2022717 to Dr. Hartmann), the South African National Research Foundation (BF-CRA 12854 to Dr. Todinanahary), the Indian Ocean Commission’s RECOS project (PhD support to Jean Aimé Zafimahatradraibe), and the LMI MIKAROKA project. Their commitment to ocean science and community-led solutions makes our work possible.

Dive Deeper

How to Volunteer for Coral Reef Restoration

Want to help restore coral reefs? Here’s how to volunteer with PIMS and the Reef Rescue Network, from dive-based restoration trips to snorkel programs, citizen science, and remote support.

Become a PADI Dive Instructor in The Bahamas | Conservation-Focused IDC

Become a PADI Dive Instructor in The Bahamas | Conservation-Focused IDC | Perry Institute for Marine Science Education & Training Ready to take your diving skills to the next level

Stream2Sea Coral Care: The World’s First Reef-Positive Sunscreen

Stream2Sea Coral Care: The World’s First Reef-Positive Sunscreen | Perry Institute for Marine Science Conservation Partners Stream2Sea Coral Care: The World’s First Reef-Positive Sunscreen Discover why PIMS has partnered with

Build a Coral Reef for the Holidays | PIMS x Partanna

PIMS is partnering with Partanna to build a 100m² carbon-negative reef. Rick Fox is matching donations up to $25k. Help us build a sanctuary for the future.

“Seafood Nation” Documentary Premiere Explores the Heart of Bahamian Culture and the Future of Fisheries

NASSAU, The Bahamas | December 5, 2025 – From the bustling stalls of Potter’s Cay to family kitchen tables across the archipelago, seafood is far more than just sustenance in

PIMS and Disney Conservation Fund Partner to Train 19 Government Divers

PIMS dive training in Nassau strengthened national coral restoration capacity across government agencies. Bahamas Dive Training Builds National Coral Restoration Capacity Last fall, between the months of September and October,