New study in Science connects chemical “turf wars” in Maine’s kelp forests to the struggles of Caribbean coral reefs — and points to what we can do next

“It’s interesting to see patterns shared between coral reefs and kelp forests that involve “chemical warfare” in a sense, which is preventing one group from reclaiming space they once filled. The critical work now is to figure out how to overcome this process to restore the original ecosystem engineers, be they corals or kelps.” — Dr. Aaron Hartmann, PIMS Senior Scientist & study co-author

A Tale of Two Forests

A healthy kelp forest is an underwater redwood grove—towering fronds, nursery habitat for fish, and a living seawall that blunts storm waves. Swap that canopy for a shaggy turf mat and you get marine scrubland: biodiversity drops, carbon draw-down falters, and coastal economies lose a natural asset. The new study pinpoints the missing culprit behind Maine’s collapse and ability to rebound: chemistry, not just heat. In cooler northeastern Maine, kelp still hangs on; farther southwest, turf has taken over and locks in its gains with toxic exudates.

What the Researchers Did

| Question | Method | Take-home Result |

|---|---|---|

| How much coastline flipped to turf? | Three-year dive surveys | Kelp persists in the coolest sector; turf dominates the rest. |

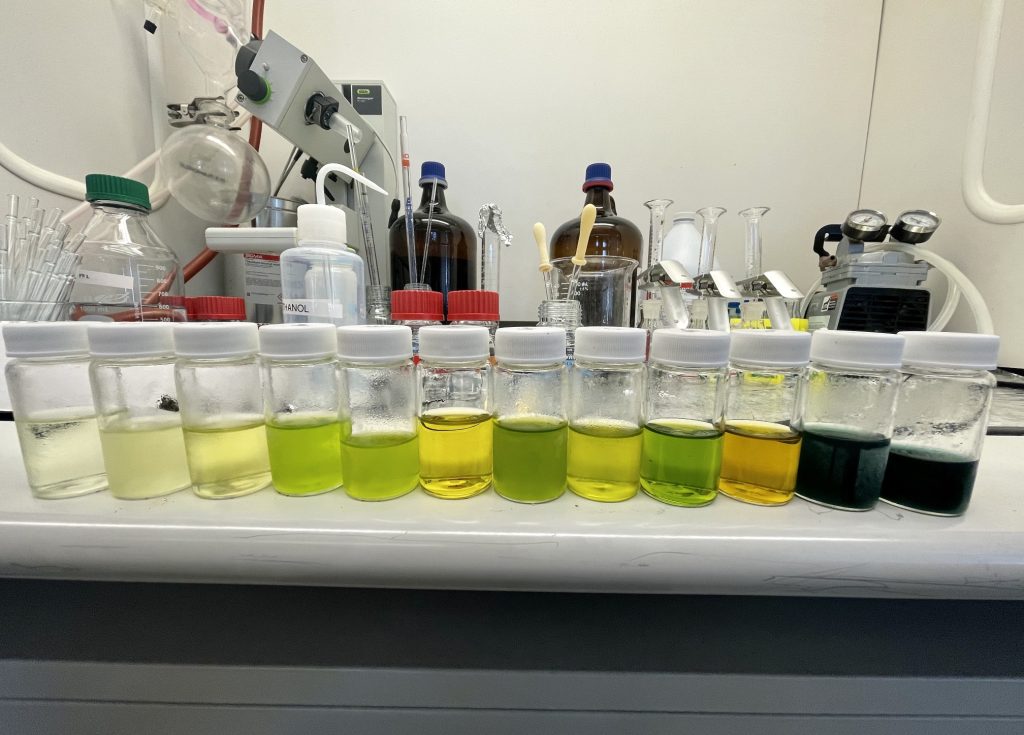

| What chemicals are present? | Non-targeted metabolomics of seawater & algae | >16,000 molecules detected; 98 % previously unknown. |

| Do the chemicals harm baby kelp (spores)? | Lab assays with turf-conditioned water & purified extracts | Survival dropped up to five-fold; growth virtually stopped. |

The Vicious Feedback Loop

- Marine heatwaves weaken adult kelp.

- Turf algae spread, releasing bioactive compounds.

- The chemical fog kills kelp babies before they can attach.

- Bare rock stays turf-coated, tightening the loop.

Which link can we break so kelp can get a foothold again?

Why Folks in the Tropics — and You — Should Care

“This shift from kelp to turf is relatively new. We’re still beginning to answer a lot of these foundational questions that have been asked and answered in, say, the coral reef ecosystem.” — Shane Farrell, a graduate student at the University of Maine and lead author on the new study.

The study detected halogenated phenols and polyacetylenes—compound families that also thwart coral recruits in the tropics. Every lesson from Maine may shorten our learning curve in the Caribbean, where PIMS teams fight similar turf outbreaks on degraded coral. Healthy kelp and coral forests aren’t just scenic; they buffer coasts from storms, feed fisheries, and lock away carbon. Lose them, and coastal communities—from Maine lobstermen to Bahamian dive guides—feel the sting.

From Petri Dish to Practical Action

The fixes start in the water: divers in Maine have begun vacuum-style turf removal campaigns combined with reseeding kelp spores on freshly cleared rock. In the tropics, similar hands-on algae removal—paired with planting coral fragments—can give reef builders a head start. Equally critical is restoring natural grazers: urchins, parrotfish, and other herbivores that keep algae cropped short. Protecting these species, or carefully restocking them where they’ve been over-fished, tackles the problem at its root. Finally, the same metabolomic “fingerprinting” used in Maine offers a new early-warning system for reefs world-wide. By scanning reef water for tell-tale molecules, managers can spot chemical turf takeovers before they become visually obvious—buying time to intervene while recovery is still feasible.

Dive Deeper

- Farrell, S. P. et al. 2025. “Turf algae redefine the chemical landscape of temperate reefs, limiting kelp forest recovery.” Science 388: 876–880. doi:10.1126/science.adt6788

- Bigelow Laboratory press release, 22 May 2025

Microscope close-ups of kelp gametophyte clumps—bright-field reveals their hair-fine structure, red fluorescence marks living cells rich in chlorophyll, and green fluorescence shows dead cells stained after turf-algae exposure, capturing the delicate line between growth and loss.

Dive Deeper

PIMS and Disney Conservation Fund Partner to Train 19 Government Divers

PIMS dive training in Nassau strengthened national coral restoration capacity across government agencies. Bahamas Dive Training Builds National Coral Restoration Capacity Last fall, between the months of September and October,

Florida’s Coral Reef Crossed a Line: What Functional Extinction Really Means for Elkhorn and Staghorn Corals

Reefs didn’t just bleach. They functionally vanished in one summer. A new Science study co-authored by researchers from the Perry Institute for Marine Science (PIMS) has found that Florida’s two

Q&A: Understanding the IDC Course at PIMS with Duran Mitchell

A former aquarist turned coral conservationist, Duran is passionate about understanding how all marine life connects. PIMS & IDC: Empowering New Dive Instructors for Marine Conservation PIMS & IDC: Empowering

Forbes Shines a Spotlight on Coral Reef Restoration in the Caribbean

When Forbes highlights coral reef restoration, it signals something powerful: the world is paying attention to the urgent fight to protect reefs. And solutions are within reach. Recently, Forbes featured Dr. Valeria

New Reef Rescue Diver Course: Volunteer in Coral Reef Restoration Abroad

Coral reefs are often called the rainforests of the sea—complex ecosystems that shelter a quarter of all marine life, feed millions of people, protect coastlines from storms, and attract travelers

PIMS & RRN Partner with Erica Lush in La Solitaire du Figaro

Racing for Resilience: PIMS & RRN Partner with Erica Lush in La Solitaire du Figaro From coral nurseries to Europe’s hardest solo offshore race; why our science belongs at sea.