Reefs didn’t just bleach. They functionally vanished in one summer.

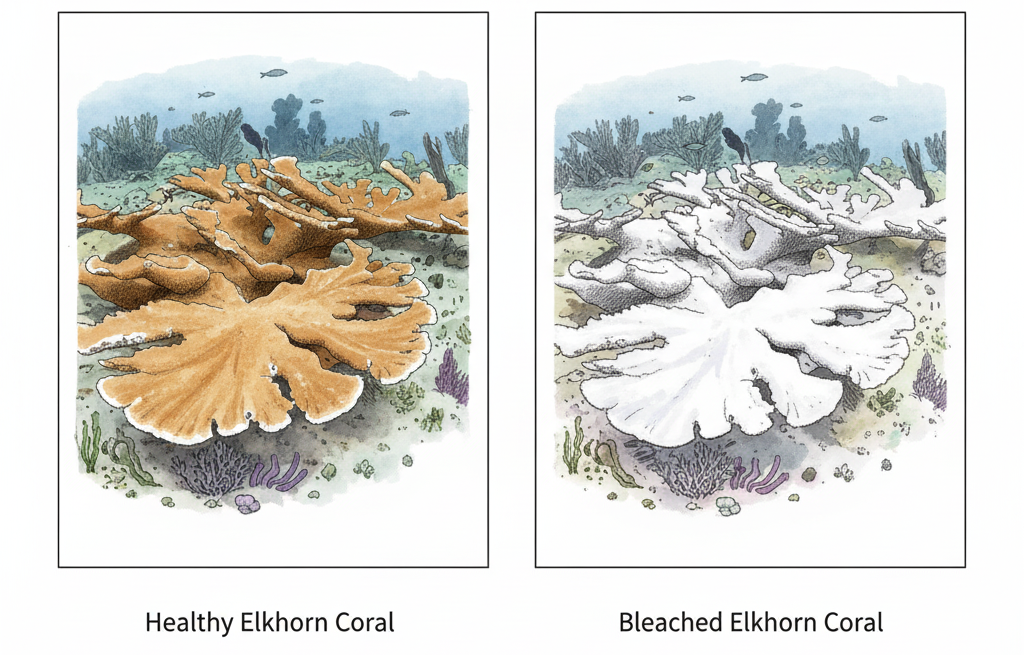

A new Science study co-authored by researchers from the Perry Institute for Marine Science (PIMS) has found that Florida’s two most iconic reef-building corals—staghorn (Acropora cervicornis) and elkhorn (Acropora palmata)—are now functionally extinct across the Florida Reef Tract. It’s a scientific threshold few expected to cross so soon, with implications for the Caribbean and beyond.

What the Study Found

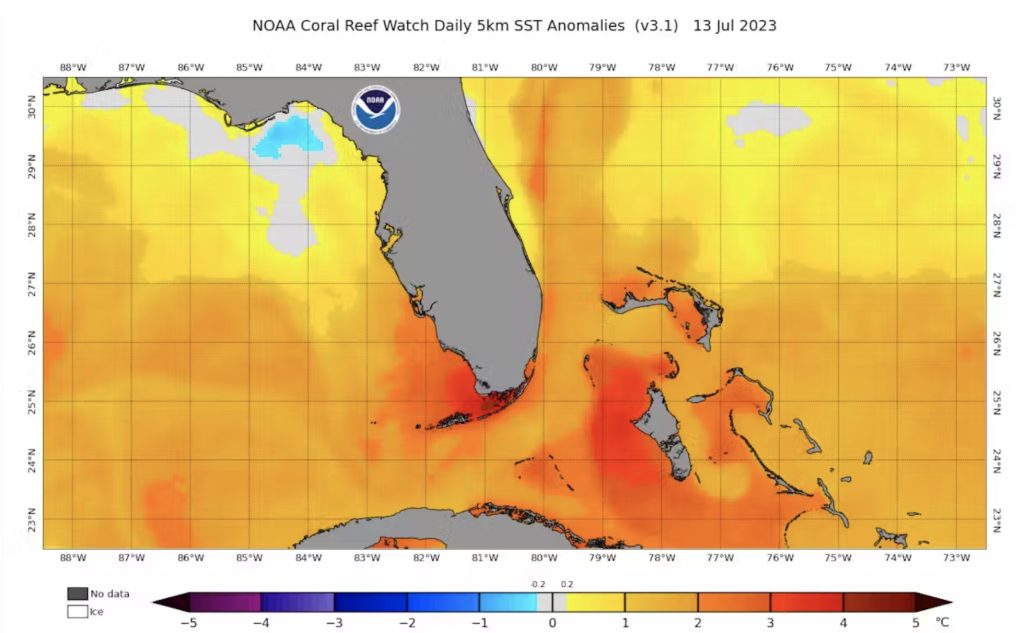

In the summer of 2023, Florida’s reefs endured one of the most intense marine heat waves on record. Sea surface temperatures exceeded 31 °C (88 °F) for an average of 40.7 days, while heat exposure was 2.2 to 4 times higher than any year since the 1980s. The result was catastrophic: 97.8 to 100 percent mortality among staghorn and elkhorn corals in the Lower Keys and Dry Tortugas.

Scientists describe this as an ecological collapse; too few remaining individuals to perform their natural roles as reef architects. The study identified a few surviving colonies farther north, but not enough to rebuild the lost reef structure. Maya Gomez, PIMS research associate and co-author of the study who is currently completing her PhD at the University of Southern California, explains that the loss of these branching species means more than coral mortality. It marks the loss of ecosystem function. Without them, Florida’s reefs can no longer buffer storms, support fisheries, or fuel coastal economies.

By the Numbers

| Metric | Finding |

|---|---|

| Avg. SST (2023) | ≥ 31 °C for 40.7 days |

| Heat stress | 2.2–4× historic levels |

| Acropora mortality | 97.8–100% |

| Reefs surveyed | ~400 |

| Corals assessed | > 50,000 |

Why This Heat Wave Was Different

Bleaching usually unfolds over months, but in 2023, heat stress arrived so suddenly that corals bleached and died within days. This was not an isolated event. Global satellite data confirmed it as the fourth worldwide mass bleaching since records began, marking a shift toward near-continuous climate stress on coral ecosystems.

In ecological terms, “functional extinction” does not mean total disappearance. It means a population has become too small to sustain its ecological role or recover naturally. The study warns of an extinction vortex, in which low numbers, inbreeding, and repeated stress events push populations further into decline.

What Can Still Work

Despite the grim data, the study also identifies pathways for hope. Pockets of healthy corals in cooler waters across the Caribbean could help seed Florida’s recovery if connected through science-led interventions such as:

-

Assisted gene flow: breeding surviving corals from different regions to restore genetic diversity.

-

Heat-tolerant genotypes and symbionts: identifying and supporting corals that can better withstand future heat waves. This is one of our primary objectives of the Reef Rescue Network, a coalition of dive shops, NGOs, and forward-thinking businesses that operate coral nurseries throughout the Caribbean with the shared goal of propagating and planting new coral life.

-

Microfragmentation and cryopreservation: rapidly propagating corals and preserving genetic material for long-term use.

-

Targeted refugia: locating naturally cooler sites that could serve as climate refuges.

These approaches depend on international coordination, clear permitting frameworks, and global action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Without tackling ocean warming, even the most advanced restoration efforts will struggle to keep pace.

Why PIMS’ Role Matters

The Perry Institute for Marine Science has long been at the forefront of coral reef research and restoration, working with NOAA, Shedd Aquarium, and universities across the Caribbean. PIMS scientists have built coral nurseries, conducted large-scale population censuses, and developed genetic banking technologies that are now informing new restoration models.

Their participation in this Science study underscores PIMS’ commitment to bridging research and implementation—turning data into direct conservation impact. Through the Reef Rescue Network and other regional partnerships, PIMS continues to scale up coral restoration and climate resilience projects inspired by these findings.

The organization emphasizes that addressing coral decline requires both innovation and collaboration. While restoration alone cannot solve climate change, combining cutting-edge science with collective global effort can still give reefs a fighting chance.

What Readers Can Do

The fate of Florida’s reefs isn’t sealed—it’s conditional. Every ton of carbon avoided, every coral fragment protected, and every new partnership moves the line back toward recovery.

You can help:

-

Advocate for climate policies that curb emissions.

-

Support marine research and restoration initiatives.

-

Follow and share updates from PIMS and the Reef Rescue Network.

-

Donate to programs that fund coral nurseries and train local restoration teams.

Mini-Glossary

DHW (Degree Heating Weeks): A measure of cumulative heat stress on corals.

Functional extinction: A population so small it no longer fulfills its ecological role.

Assisted gene flow: Moving or breeding corals from different populations to restore genetic diversity.

Further Reading

Science article (DOI: 10.1126/science.adx7825) | The Conversation explainer (October 2025)